Meet the artists

How did a teacher from Maine and an art class in the South Bronx became a world-renowned artist collective? Hear from artists Tim Rollins and Angel Abreu.

-

Tim Rollins and K.O.S. Courtesy the artists and Lehman Maupin New York and Hong Kong. Rollins: I'm Tim Rollins. I'm a native Mainer, of many generations of Mainers. And, I just want to tell you how I became an artist.

I fell in love with the idea of education as a medium.

Painters use paint.

Printmakers use printmaking. But I love the idea of education as a medium. That's how I got involved with K.O.S.Abreu: It's funny, I actually avoided going to IS52—Intermediate School 52—where Tim taught for two years. It's that school that only three blocks away from my apartment building.

And that three-block walk was treacherous, littered with drug dealers, gangs, and all kinds of really bad things.

And I remember that first day, I walk in and... paper in the hallways, people being rowdy. But as my class approached Room 318, there's this collective hush. And I remember thinking, "OK, so what exactly is going on?"

Rollins: When I first met Angel and the other young students, I said, "You know what? I'm not a dogooder. I'm not a missionary, but I'm on a mission."

Abreu: A month later, Tim met my parents at parent-teacher night and he explained KOS and this thing he was doing after school; I didn't quite get it. I thought it was some afterschool program, but I really… I was really an art kid. And there was this cultural bubbling going on with hip hop and graffiti and all this.

In a lot of ways, if you could draw, you're a hero.

And so yeah, I was all for going to the studio. Had no idea what to expect.

Tim would drag us to MoMA, and the Met, and the Whitney, and the Guggenheim and the simple things like going to a restaurant.

You know, as an 11-, 12-year-old, these are life experiences that mold you.

That's really part of it, the trips. And, you know, essentially traveling with these books, these things that didn't belong to us.Tim would always quote the great WEB DuBois quote from "The Souls of Black Folk," that says, "I sit by Shakespeare and he winces not."

And I remember feeling… thinking, "What? What does that mean?" initially. And then it made sense. These books weren't written for PhD candidates. They're written for all of us. I took that to heart.

Rollins: We didn't make art to be cute. We didn't make art to win awards, although we have. We made art to survive. We made art to survive, psychologically.

At a certain point, financially, and in a strong point, physically.

-

Amerika - Everyone is Welcome! (after Kafka), 2002 Rollins: I know I learned a lot from going to quilting bees in rural Maine. And these women would get together and they would try to blow each other away with their patch. But when you put it all together, it's absolutely beautiful and stunning. It's democracy made visible.

Abreu: Right, I mean it's fierce. The final product is beautiful, but the making is fierce. You want your middle spot. And that's kind of how it was for us initially. We would battle.

And the amazing teaching tool that Tim used was actually based on Amerika after Frans Kafka, and this whole notion of if a golden horn could represent who you are, what would that horn look like? And we had hundreds and thousands of these horns all over the studio. It was from there that we...it was a pretty democratic process. We go through all the drawings and the studies. And we’d choose, kind of choreograph where everything is going to go.

Rollins: There's certain sections of the books that inspire. They actually inspire inspiration. And that’s the ones that generate the ideas, and the visuals of what we come up with.

Angel: Right, we're not illustrating, we're adding to the conversation, as we like to see it. It's almost like we're having a seance with Twain, with DuBois, with Kafka. I mean, that's really how we see it. We see that they are also collaborating with us.

You know, it wasn't until years later. I knew what we were doing then was really special, especially because every single day, Tim would tell us, "We're making a history." Literally every single day. And, you know, as an 11-, 12-year-old, you're thinking, "Wow! That sounds great. You're crazy, but that sounds great." But the thing is that, you know, there was no condescension from Tim. There was no patting on the head like. No. He would let us know, "You can do better. You can do better than this," or, "Wow! That's really fantastic," when we merited it. That level of respect, that reciprocation of respect that we had, I never had that from an adult before.

Rollins: And, after over 30 years, we feel like we’ve just started.

Zoom In

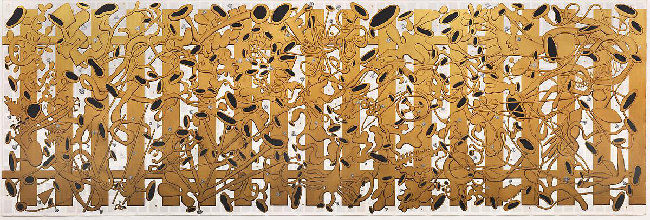

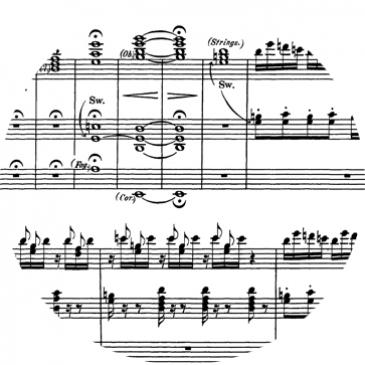

Tim Rollins and K.O.S.’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream consists of 200 pages from Felix Mendelssohn’s symphony score overlaid with more than 800 dripped, dyed, and painted flowers. Zoom in to examine details. Look up to compare the details to the full composition as a whole.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2016

Tim Rollins, K.O.S and the PMA

Learn more about how and why A Midsummer Night’s Dream came to the PMA.

-

“What would you do if I gave you a wall at the Portland Museum of Art?” -PMA Chief Curator Jessica May

Although rock bands can work collaboratively for decades, the world of visual art has few truly long-term collectives. Yet Tim Rollins and K.O.S. have been making work as a team for more than 30 years. What began as a middle school after-hours program has, for many of them, become a lifelong connection.

This wall-covering, however, is a radical shift for the collective. Since the 1980s, the group’s work has been physically created using the pages of a book, score, or speech, mounted on canvas. For A Midsummer Night’s Dream, however, they digitally layered dipped and dyed paper on the musical score in collaboration with the textile development firm, Maharam. “(With) the technology now,” Rollins says, “this is not a reproduction. This is not a copy. This is the real, real thing.”

What the process creates is a wall-covering in the tradition of large-scale murals. The building in which you stand is perfect for this type of art. Its architect, Henry Cobb, imagined a museum where there is a sense of discovery as you move through galleries of is different shapes and sizes. The windows and overlooks encourage unexpected encounters with works of art.

-

Making it into Museums

The Kids of Survival (K.O.S.) were formed in the South Bronx in the 1980s. These students—mostly of color, many working class or poor—were considered “at risk” and thus essentially written off. But their art teacher, Tim Rollins, saw great potential in them. One of Rollins’ early participants, Angel Abreu, recalls:

“Tim would always quote the great W.E.B. DuBois from The Souls of Black Folk: ‘I sit by Shakespeare and he winces not.’ I remember thinking, ‘What? What does that mean?’ initially. Then it made sense. These books weren’t written for Ph.D. candidates. They’re written for all of us.”

In less than a decade, the group’s paintings were in the collections many museums and galleries, which is very important. In Abreu’s words,

“These things are going to survive. We’re going to be long gone, and they’re still going to be in these institutions that are cool in the summer, and warm in the winter. They’re going to be treated so well, and we’re going to continue.”

Hear the music

Felix Mendlessohn took inspiration from William Shakespeare’s text to create his A Midsummer Night’s Dream. A century later, Tim Rollins and K.O.S. were inspired by both works of art. This recording by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Seiji Ozawa, with narration by Dame Judi Dench is the version Rollins played in his workshops.

-

Written 16 years prior to the remainder of the music, the Overture sets the stage for the drama that will follow. With a fleeting, almost rushed quality, we are transported to the magical woods near Athens of Shakespeare’s play. We anticipate the drama and chaos that is to come.

Felix Mendelssohn,

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Overture (11’55) -

Here the fairy king Oberon plots his revenge on Titania, the fairy queen. Oberon’s jealously over her attention to a page boy sparks him to enlist the help of the mischevious Puck to cast a spell on Titania, so she will fall madly in love with the next creature she sees. Unfortunately for her, this creature is Nick Bottom, a man who was given a donkey’s head by Puck.

Felix Mendelssohn,

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, March of the Fairies (1’52) -

Puck has exhausted each of the four lovers—Hermia, Helena, Lysander, and Demetrius—into a deep sleep. The music evokes the warmth and drowsiness of a summer night. When they awake, each will fall in love with the right person and all will be right with the world.

Felix Mendelssohn,

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Nocturne (6’21) -

This jubilant and now-popular wedding march marks the transition from the magic-filled forest to Athens, and from night into day. The two young couples join in the wedding celebration of Theseus and Hippolyta.

Felix Mendelssohn,

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Wedding March (5’07) -

As day breaks and the young lovers have retreated from the magical forest to the human world, Puck closes out the action with one of Shakespeare’s most famous monologues. Mendelssohn repeats the four chords from the very beginning of the Overture, encouraging us to consider what is magic and what is reality.

Felix Mendelssohn,

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Finale (5’48)

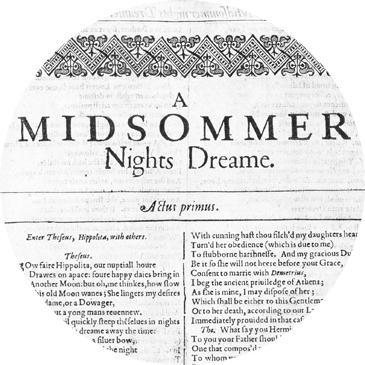

Read the text

Tim Rollins and K.O.S. were inspired by William Shakespeare’s original A Midsummer Night’s Dream, as well as Felix Mendelssohn’s musical interpretation of it. In the text, they honed in on the character of Puck, the play’s most mischievous sprite.

-

The dipped paper flowers that dot across the work’s surface represent the magic flower that creates so much chaos in the story; drops of its nectar cause characters to fall in love with the next creature they see. Ugliness is made beautiful, indifference becomes infatuation, and chaos ensues. But the students who created them did not simply make flowers. Rollins asked them for more, saying:

“Listen. This is what I want you to do. I want you to become Puck. The little rascal. The one that just loves to transform things, just for the sheer joy of it…Just become Puck.”

Swipe right to meet, or re-meet, that errant sprite.

-

We first encounter Robin Goodfellow, nicknamed Puck, as he and a fairy meet by chance as they wander “over hill, over dale, through bush, through brier,” serving their fairy king and queen, Oberon and Titania.

FAIRY

Either I mistake your shape and making quite,

Or else you are that shrewd and knavish sprite

Call'd Robin Goodfellow: are not you he

That frights the maidens of the villagery;

Skim milk, and sometimes labour in the quern

And bootless make the breathless housewife churn;

And sometime make the drink to bear no barm;

Mislead night-wanderers, laughing at their harm?

Those that Hobgoblin call you and sweet Puck,

You do their work, and they shall have good luck:

Are not you he?PUCK

Thou speak'st aright;

I am that merry wanderer of the night.

I jest to Oberon and make him smile

When I a fat and bean-fed horse beguile,

Neighing in likeness of a filly foal:

And sometime lurk I in a gossip's bowl,

In very likeness of a roasted crab,

And when she drinks, against her lips I bob

And on her wither'd dewlap pour the ale.

The wisest aunt, telling the saddest tale,

Sometime for three-foot stool mistaketh me;

Then slip I from her bum, down topples she,

And 'tailor' cries, and falls into a cough;

And then the whole quire hold their hips and laugh,

And waxen in their mirth and neeze and swear

A merrier hour was never wasted there. -

Oberon and Titania are in a fierce quarrel over a page boy. The queen’s devotion to the boy has made Oberon suspicious, and his suspicion has made her furious. Here, he enlists Puck to plot his revenge.

OBERON

Flying between the cold moon and the earth,

Cupid all arm'd: a certain aim he took

At a fair vestal throned by the west,

And loosed his love-shaft smartly from his bow,

As it should pierce a hundred thousand hearts;

But I might see young Cupid's fiery shaft

Quench'd in the chaste beams of the watery moon,

And the imperial votaress passed on,

In maiden meditation, fancy-free.

Yet mark'd I where the bolt of Cupid fell:

It fell upon a little western flower,

Before milk-white, now purple with love's wound,

And maidens call it love-in-idleness.

Fetch me that flower; the herb I shew'd thee once:

The juice of it on sleeping eye-lids laid

Will make or man or woman madly dote

Upon the next live creature that it sees.

Fetch me this herb; and be thou here again

Ere the leviathan can swim a league.PUCK

I'll put a girdle round about the earth

In forty minutes.After Puck leaves, Oberon reveals the details of his plot: to wait until Titania falls asleep and drop the liquor into her eyes so she will fall in love with the next creature she encounters. He plans to release her from her drugged infatuation in return for the page boy.

-

As Oberon waits for Puck’s return, he encounters Helena in pursuit of the man she loves, Demetrius. But Demetrius loves Hermia, who has eloped into the woods with her love, Lysander. Oberon takes pity on Helena, just as Puck returns.

OBERON

I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,

Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows,

Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine,

With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine:

There sleeps Titania sometime of the night,

Lull'd in these flowers with dances and delight…

And with the juice of this I'll streak her eyes,

And make her full of hateful fantasies.

Take thou some of it, and seek through this grove:

A sweet Athenian lady is in love

With a disdainful youth: anoint his eyes;

But do it when the next thing he espies

May be the lady: thou shalt know the man

By the Athenian garments he hath on.

Effect it with some care, that he may prove

More fond on her than she upon her love:

And look thou meet me ere the first cock crow.PUCK

Fear not, my lord, your servant shall do so. -

Oberon’s intervention causes more chaos. Puck mistakenly anoints the eyes of the wrong Athenian man, making Lysander fall instantly in love with Helena and inexplicably spurn his bride-to-be, Hermia. Oberon drags Puck back into the woods to see the turmoil he has created.

OBERON

This is thy negligence: still thou mistakest,

Or else committ'st thy knaveries wilfully.PUCK

Believe me, king of shadows, I mistook.

Did not you tell me I should know the man

By the Athenian garment be had on?

And so far blameless proves my enterprise,

That I have 'nointed an Athenian's eyes;

And so far am I glad it so did sort

As this their jangling I esteem a sport.Oberon is less amused, and orders the hobgoblin to lead the lovers on such a chase that they would fall into exhausted sleep. When they woke—love potion removed—it would all seem a bad dream. Puck complies, relishing the mayhem.

PUCK

Up and down, up and down,

I will lead them up and down:

I am fear'd in field and town:

Goblin, lead them up and down. -

The four young lovers return to Athens and recount their tale to their human king and queen, Theseus and Hippolyta. Theseus’ monologue, in particular, resonated with Rollins’ creative process.

HIPPOLYTA

'Tis strange my Theseus, that these

lovers speak of.THESEUS

More strange than true: I never may believe

These antique fables, nor these fairy toys.

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

The lunatic, the lover and the poet

Are of imagination all compact:

One sees more devils than vast hell can hold,

That is, the madman: the lover, all as frantic,

Sees Helen's beauty in a brow of Egypt:

The poet's eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Such tricks hath strong imagination,

That if it would but apprehend some joy,

It comprehends some bringer of that joy;

Or in the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear!HIPPOLYTA

But all the story of the night told over,

And all their minds transfigured so together,

More witnesseth than fancy's images

And grows to something of great constancy;

But, howsoever, strange and admirable. -

Puck ends the play with this monologue to the audience, which has become one of Shakespeare’s best-loved monologues.

PUCK

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumber'd here

While these visions did appear.

And this weak and idle theme,

No more yielding but a dream,

Gentles, do not reprehend:

if you pardon, we will mend:

And, as I am an honest Puck,

If we have unearned luck

Now to 'scape the serpent's tongue,

We will make amends ere long;

Else the Puck a liar call;

So, good night unto you all.

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.

Works by Tim Rollins and K.O.S.

Hear Tim Rollins and Angel Abreu speak in depth about specific works from their 30-year career. Discover why certain subjects were chosen, the significance of those subjects, how their style evolved, and the stories of creating these works of art.

-

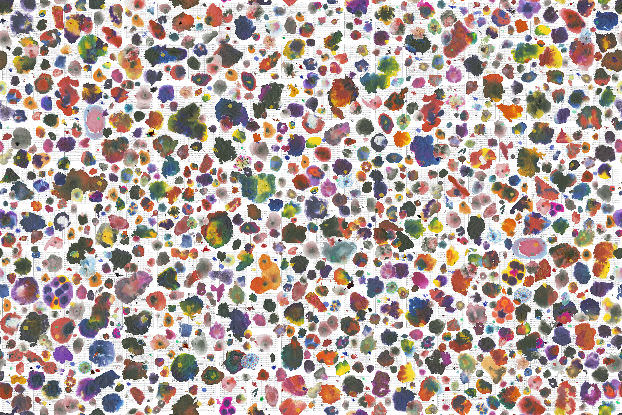

A Midsummer Night's Dream, 2016 Abreu: Essentially, for those who don't quite understand what we do, is we will take a book, or score, and carefully adhere it onto the canvas in a gridlike fashion, and then we’ll do whatever it is that we do on top of it. And so for the Midsummer Night's Dream, we used this beautiful tied Mulberry paper that's almost like… it’s almost like toilet paper. It's a little stronger, but it's just as thin, and we fold those into two. And we use beautiful inks, and juices, and whatever we can find to make these flowers, essentially, and when we undo those you've got basically a mirror image, and it's to signify both the fantasy world, and the real world that's at play in the play.

-

Diary of a Slave Girl (After Harriet Jacobs), 1998 Rollins: Harriet Jacobs spent seven years in a room that's nine by seven feet in an attic, in hiding from her slave master. So that was something about the size that we could get. But the painting was completely inspired by the interesting painter named Winslow Homer.

And Winslow Homer has a painting called Dressing for the Carnival. And it’s one of the very few depictions we have of the Johnkannaus.

And it was when slaves could actually party and they dressed in these amazing, amazing outfits with all these beautiful ribbons and found fabric, anything they could find, sewn on to muslin sheets.

And it all came together like that. If you had this very torturous text, to have these beautiful ribbons festooned on the text…. And each ribbon is a self-portrait. We chose the colors individually.

Abreu: Well, I mean, in a lot of ways, it's kind of a metaphor of us. This whole notion that because we come from this abject poverty, that this is what we have to reflect in our work. And so . . . no, we want to celebrate the beauty.

Rollins: We've seen a whole lot of ugly. We don't need to do ugly. No. We need to take our situation and everything we've been through to make something beautiful, because when you get right down to it, I believe—and I know I think the whole K.O.S. family believes—that only beauty can change things.

-

The Great Gatsby (after F.S. Fitzgerald), 2011 Abreu: Gatsby is one of those books that's been on the back burner for years. We just couldn't figure out what it was going to look like. We want to do something that's really subtle, that graphically doesn't read quite like the book, but will set the tone, set the mood, kind of like Fitzgerald.

And so we decided to dig down deep into the book, and look at color and certain ways Fitzgerald sets certain moods, depending on what they're wearing.

Rollins: There's a lot of color symbolism in the book.

Abreu: The green is quite obvious. It's about money, and greed.

Rollins: But it also was a beacon, from the book.

Abreu: That's the beacon.

Rollins: It's the beacon. I love what we do, because it's about wonderful contradictions. You know?

-

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—Asleep on the Raft (after Mark Twain), 2011 Rollins: We took the original edition of Huck Finn, and there's a guy named Kemble. He did the illustration. And in the beginning of the book, you see depictions of both Huck, it looked like a little hillbilly, white trash boy, and then Jim, who looked like a minstrel. And what is fascinating, is you go to the end of the book, and they are depicted as fully human, and beautiful. It was like, "Wow, look at that transformation." So something happened in the making of that.

It was about the relationship between Huck and Jim. And this impossible, impossible love. That kind of Agape love. You love someone who doesn't look like you, doesn't talk like you, doesn't walk like you. You love someone no matter what.